At Waikanae Anglican, we have a rich heritage and spiritual DNA that we draw upon. We recognise that our history shapes who we are, and that we are part of a big eternal story, as well as a local one.

We are thankful for those who have gone before us in 170 years of ministry and mission.

Our Parish’s mission station origin dates back to November 1839. Octavius Hadfield was commissioned by the Church Missionary Society base in the Bay of Islands in response to a request for a missionary by the Tangata Whenua. He did not come to the Kapiti Coast to start a mission but to encourage the existing work of God amongst the Maori living in Waikanae and Otaki.

And this is how our story unfolds..

In the 1830’s a Maori young girl called Tarore became a believer, and was given a small copy of St. Luke’s gospel as a gift . Tarore treasured this gift and kept it in a tiny bag around her neck. Tragically she was murdered on 19th of October 1836 by a man called Uita from a tribe who hated Tarore’s people, who took the little copy of Luke’s gospel still wrapped in its little bag back to Rotorua . He could not read so asked a slave to teach him. As he learned to read the gospel of St. Luke he was soundly converted and went to Tarore’s father to ask forgiveness which caused a lasting peace between the two waring tribes. This gospel of St. Luke still had not finished its purpose, because the slave who had taught Uita to read shared with two Maori chiefs who lived in Waikanae, about Christianity and sent for the copy of St. Luke’s gospel from Uita. As they read the story of Jesus Christ in their own language they too were converted and walked all the way to the Bay of Islands, to ask for a missionary – soon there was over 500 people daily at morning and evening prayer. When the Maori and Pakeha people built our church – there was no debate about naming the Church after St. Luke, whose gospel had changed so many lives. Who would have thought that a little girls faith, would by a series of circumstances impacted two waring tribes and brought peace, and brought transformation of life in Waikanae. She is honoured by the Anglican Church on pg 23 of the NZ Prayer Book on Oct. 19 as one of NZ’s first martyrs.

St. Luke’s was shifted to its present site in 1906 after being part of the marae, shifting at the same time the marae relocated.

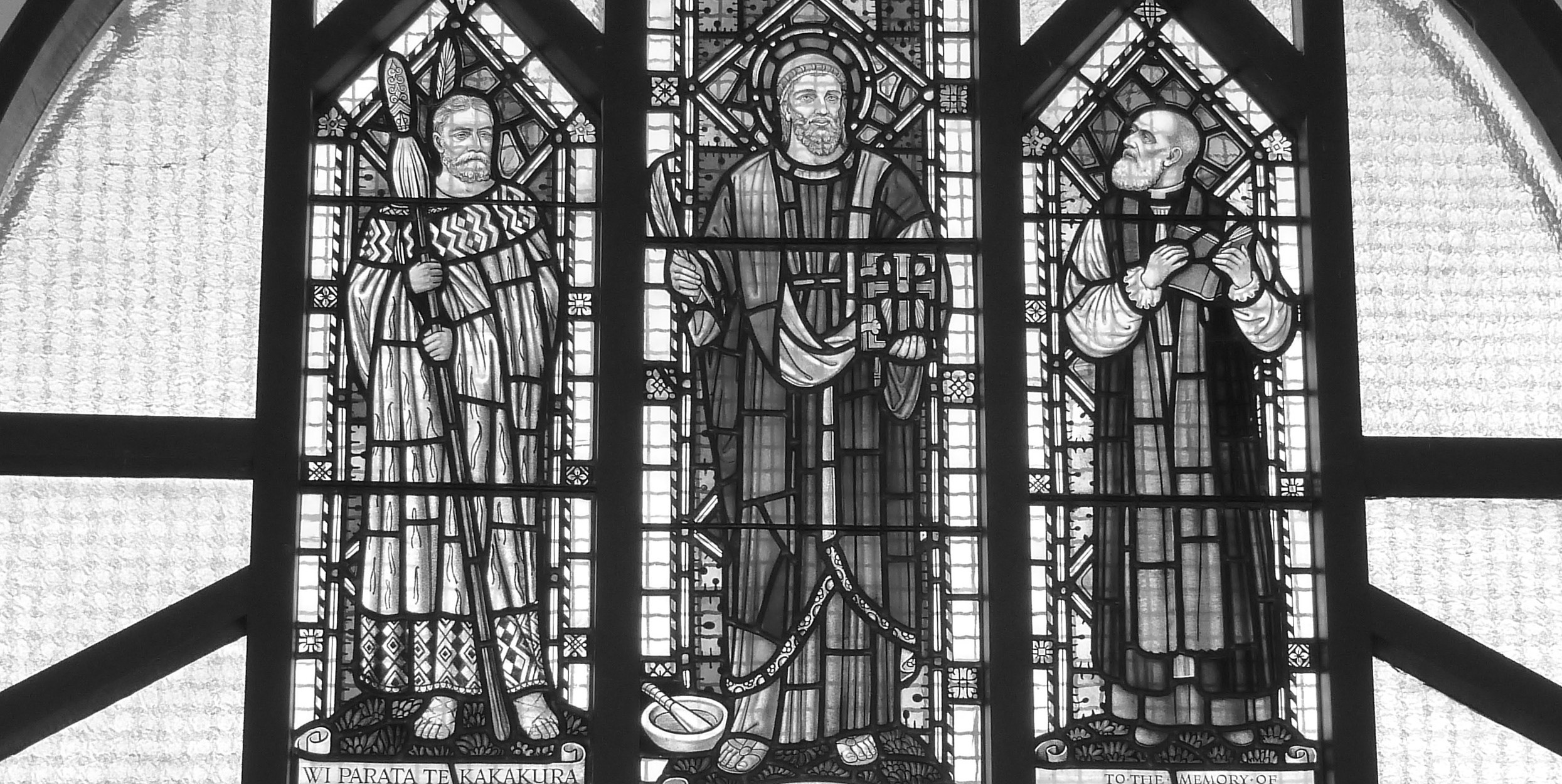

Wi Parata as show on the window at St Luke’s

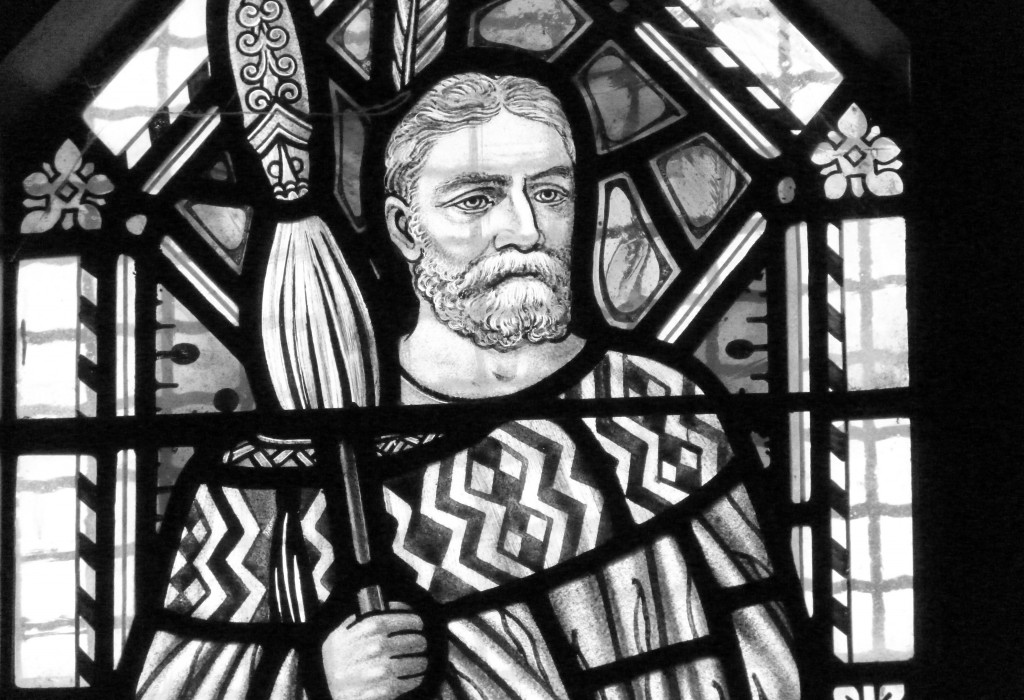

Octavius Hadfield as show in the window at St Luke’s

The beginnings of Christianity on the Kapiti Coast

Traditionally, war parties would go on the attack in the fighting season after food gathering in the late summer, in order to avenge an insult or promote tribal honour. Fighting would continue until honour was satisfied, or food supplies had run out, and would then be renewed in the next season. As with all warfare, success brought glory and booty to the victor and misery to the fallen. In the case of Maori tribal warfare, defeat meant enslavement, pillage of food supplies and other property, and the burning of villages. The victors would celebrate with a cannibal feast of executed captives. The introduction of muskets turned this pattern – previously often no more than brief skirmishes involving mere dozens of people – into scenes of massacre and widespread desolation; whole districts were depopulated.

Te Rauparaha, with musket-armed warriors, had, during the late 1820s and 1830s, carried out a series of raids on the Ngai Tahu in the northern half of the South Island and exiled and enslaved hundreds. All the principal Ngai Tahu pa were destroyed – at Kaikoura, Kaiapohia (Kaiapoi), and at Onawe Bay and elsewhere on Banks Peninsula. The captives who had survived cannibal feasts were taken to the Kapiti coast and put to work producing and harvesting flax and potatoes. Ships flocked over from Sydney to take back cargoes of these products in return for muskets, which would enable Te Rauparaha to carry out further devastation. Also offered for sale was a lucrative supply of tattooed heads. Slaves who had caused some offence would be handsomely tattooed and slain and the heads supplied to traders. They fetched a good price in muskets. The Kapiti coast was known for its cruelty. Kapiti (or Entry) Island was Te Rauparaha’s base to which he brought back the captives from his devastating raids on the South Island.

It was into this environment that the Christian gospel came to the Kapiti coast. The message of forgiveness and reconciliation in Tarore’s little Gospel of St. Luke was already taking root before Octavius Hadfield arrived.The Gospel was first brought to the south of the North Island in the 1830s by Maori catechists who had been educated in Anglican mission stations in the north. The Maori people recognised the power of the written word and many of their leaders were keen to learn to read the English language and to discover the Christian Faith. Waikanae Beach became the first centre for Anglican worship, led by Maori catechists in a wharenui/church building in the Waikanae Pa, many months before the arrival of Revd. Octavius Hadfield in Nov. 1839. (Dr. Ernest Dieffenbach visited this wharenui/church a month before Hadfield and Williams arrived in Nov. 1839.) This extremely large Waikanae Pa contained a labyrinth of “courts and divisions” and its stockade was nearly two km. in circumference! At this time there were two other local Ngati Awa pa, one located 2km south at Arapawaiti and the other just north across the river mouth at Waimeha.

One of the known Maori catechists in the Kapiti district was Ripahau (baptised Hohepa) of Ngati Raukawa, who is reported to have “taught the Ngatiawa everything he had been taught at the Mission School at the Bay of Islands – which included the basic doctrines of the Christian Faith, how to sing the Prayer Book Services and how to read and write.” Ripahau is believed to have brought Tarore’s Gospel of St. Luke as well as other Christian books to Kapiti.

Early in 1839, Tamihana, the son of warrior chief Te Rauparaha, and his cousin Matene Te Whiwhi, who had been taught how to read and write and were introduced to the Gospel by Ripahau, travelled the one thousand plus kilometres journey to the Bay of Islands to plead for a missionary to be sent to the Kapiti Coast. Revd.Henry Williams agreed, at the urging of the recently priested Octavius Hadfield, a 25yr. old chronic asthmatic, and they sailed south to Wellington Harbour and travelled overland to Waikanae Pa. It is recorded that they were enthusiastically welcomed by as many as a thousand Maori catechumens, as well as by an even greater numbers of fleas and mosquitoes! Riwai Te Ahu became Hadfield’s able assistant, his Maori teacher and Kapiti’s first lay reader.

The wharenui soon became too small for Hadfield’s congregations and a “very beautiful church”, with a 76ft. ridgepole from the Otaki bush donated by Te Rauparaha, was built at Waikanae Pa (1841-43).

It is evident that the youthful Hadfield had quickly earned the respect and friendship of the much feared warrior known by the European settlers as the “Napoleon of the South Pacific”. The marked site of this building today bestrides Mazengarb Road, Kenakena, on the southern side of the Waikanae River estuary.

Bishop Selwyn confirmed one hundred and twenty Maori there in late 1843 and was most impressed by its spaciousness. It served as a model for the slightly larger Rangiatea church, built eight years later in Otaki, and was similarly as impressive. Little more than a year after its completion, when Hadfield was so ill in Wellington that he was not expected to recover, the Revd. Richard Taylor observed that “this beautiful Maori edifice was rapidly hastening to decay” and threatened by drifting sand.

Octavius Hadfield’s first church on the Kapiti Coast was located at Kenakena Pä, in Waikanae. In many ways it was the model for Rangiatea. Completed by 1843, the church greatly impressed Te Rauparaha, who was a frequent visitor to Hadfield’s early services. According to the missionary the Reverend Richard Taylor, Te Rauparaha was so taken with the church that he vowed to build a ‘still finer one in his pa’ at Otaki.

Like Rangiatea, the Waikanae church had three large central posts, tukutuku panels, and kowhaiwhai rafter designs – features typical of a decorated meeting house. The Waikanae church was approximately 71 feet x 36 feet.

With the return of Te Ãti Awa to Taranaki in 1848, the Waikanae church fell into decline. By 1851, it had been abandoned, and the recently completed Rangiatea had taken a firm root as the centre of Christianity on the Kapiti Coast. The sketch above by Thomas Bernard Collinson is the only surviving image of the Waikanae Church. The sketch shows the deserted Waikanae Church and Pä in 1849. In the previous year, Te Āti Awa had left Waikanae and returned to their ancestral lands in Taranaki, in order to protect their claim on the land at Waitara, which Governor Grey was attempting to acquire for Pākēhā settlement.

The exodus of Te Ati Awa led to a shift of activity from Waikanae to Otaki. The Waikanae church suffered from neglect, and the continuously encroaching sands threatened to overwhelm the failing church walls. By 1851, it was in ruins. In 1961, the remains of the church were uncovered during preparations for a subdivision in Paraparaumu’s Mazengarb Road. Selwyn Hadfield, a descendant of Octavius, salvaged a piece of wood from the remains and carved a decorated lectern for Rangiatea. Sadly, the lectern was destroyed in the fire which razed Rangiatea in October 1995. A litany desk which was probably came from the original Waikanae church, and was used as a pulpit in Rangiatea for many years, was returned to Waikanae Beach (St. Michael and All Angels’ church) in 1954 and so escaped destruction in the Rangiatea inferno!

By 1848, an influenza epidemic and tribal migration had drastically reduced the considerable Maori population in Waikanae to a total of about one hundred. This hapu, under the leadership of the Parata whanau, relocated to Tuku Rakau on the northern bank of Waikanae River, a kilometre upstream from the Waikanae Pa By the following year, Hadfield was remarkedly restored to health and returned to his Waikanae Beach church to find the sand level was now above the windows on one side! The base for his future ministry had now moved to Otaki where, in response to the 1848 challenge of the ageing Te Rauparaha, following his release from 18 months illegal imprisonment, Rangiatea was built (1849-51).

For about forty years, regular Anglican worship in Waikanae was largely conducted by Maori lay readers, with support from Hadfield and other clergy, in the Tuku Rakau wharenui, Waikanae Beach. In 1877, the second Maori church was built in Tuku Rakau by Wi Parata Te Kakakura. Ten years later, this Maori Church was moved to its present site across the recently built Manawatu and District railway line to serve the hapu which had relocated to Parata Township – subsequently named Waikanae Township. This church was later gifted to the Wellington Diocese by the Parata family and consecrated in 1906 in the name of St. Luke. The original floor and northern wall of the Tuku Rakau church can still be seen in the much extended St. Luke’s of today.

Matene Te Whiwhi was the son of the famous Ngati Toa chieftainess Te Rangi Topeora. Born in Kawhia, he migrated to the Kapiti Coast during the first Ngati Toa migration in 1821. As a young man, Matene participated in marauding Ngati Toa war parties on the Kapiti Coast. Because of his chiefly rank and exceptional personal abilities, he sometimes acted as a ‘go-between’ during tribal peace settlements.

Matene became a Christian and was baptised by Hadfield in 1841. In 1843, he too became a missionary. Matene was one of the tohunga responsible for performing the necessary incantations for felling and transporting the trees used in the building of Rangiatea. He was a faithful supporter of the church all his life, and died at an advanced age at Otaki on 29 September 1881. He is buried at Rangiatea.

Tamihana Te Rauparaha, also known as Katu, was the only surviving son of Te Rauparaha. Born at Okoki pā, Waitara, he was carried on the back of his mother Te Ākau to the Kapiti Coast during Ngati Toa’s historic migration from Kawhia in 1821. Although he never acquired the English language, Tamihana was quick to adopt European customs and is seen – here wearing the attire of an English gentleman.

Tamihana visited England in 1851, and was presented to Queen Victoria. On his return to New Zealand, he and Matene lobbied to establish a native monarchy based on the British model. This was to become the Kīngitanga movement. His penchant for things European – eventually estranged him from the affections of his people. He died in 1876, and is buried alongside his wife, Ruta, in an unmarked grave at Rangiatea.

It was not long before Tamihana Te Rauparaha and Matene Te Whiwhi, with encouragement from Hadfield, determined to go to the South Island. They would take the message of God’s grace which they had learned and experienced, and give evidence of what God had done among Te Rauparaha’s people by promising the return of the remaining captives. Tamihana Te Rauparaha has given us his own record of this remarkable turn of events in the book he wrote about his father, The Life and Times of Te Rauparaha. This is the story in his own words.

(We) “managed to obtain the services of Rev. Octavius Hadfield and then returned to Kapiti to instruct the tribes of the district in the gospel.

After a time Matene and I decided to take the message to the Ngai Tahu. Te Rauparaha was very angry with us for going to the Ngai Tahu in Te Waipounamu [the South Island] before he had obtained revenge for Te Puohu’s death at Murihiku. Neither of us was worried about the anger of our father – Matene was Te Rauparaha’s grandson – and we travelled by boat to Port Cooper [Bank’s Peninsular], Whangaroa, Moerangi.

Otakou [near Dunedin] and Ruapuke Island [a small island near Stewart Island which was a surviving Ngai Tahu stronghold]. Soon all the Ngai Tahu there believed in the true God of heaven.

Matene returned home after Ruapuke but I went on to Rakiura (Stewart Is), Ngawhakaputaputa and Te Kapu. The Ngai Tahu chiefs would keep asking me: ‘Is your father planning to come here and kill us and take our lands?’ I told them: ‘No, he will not come, for I have brought peace with the words of the Lord.’ I was away for a year at Murihiku [Southland] and Rakiura before returning home to Kapiti. We had made peace with the Ngai Tahu, so this was the end of Te Rauparaha’s plans to keep fighting them.” Tamihana Te Rauparaha’s modest words conceal an undertaking that was fraught with danger. To speak words of reconciliation to the Ngai Tahu was the last thing the old chief, his father, wanted. He was burning to avenge on the Ngai Tahu the death of his friend and comrade-in-arms, Te Puoho. After Te Rauparaha had massacred the inhabitants of the pa at Kaipohia and Onawe Bay, he determined to go further south and wipe out the remnants of the Ngai Tahu tribe. Before he could set out, Te Puoho, seeing an opportunity for personal glory, hastened south himself to ‘scale the fish by the tail’ and bring back Ngai Tahu captives ‘like cattle’. When he got as far south as Murihiku, he was taken by surprise by the great Ngai Tahu chief, Tuhawaiki, and shot dead in battle. The custom of utu required Te Rauparaha to avenge this death and it was not surprising that his son should describe him as being ‘very angry’. Te Rauparaha’s anger was a fearful thing and, although Tamihana says that he and Matene were not worried, they were taking a great risk in trifling with the great chief’s ire and obligations.

An even greater risk was for the two young men to venture unarmed and on their own anywhere near Ngai Tahu territory, 1et alone going in to their remaining strongholds at Otakou and Ruapuke Island. Utu required that both be killed without mercy. But these two men had experienced the change that God’s grace had brought to their own lives, and had witnessed the dramatic changes brought by the gospel to their own community at Otaki. As a young teenager, Tamihana Te Rauparaha had been taken by his father on many of his expeditions against the Ngai Tahu. He knew the dreadful suffering and havoc that his father had brought to these people and he was determined, despite the risks, to do what he could to bring the warfare to an end. The coming of the gospel to his people at Kapiti had also weakened Te Rauparaha’s resolve to wipe out the Ngai Tahu. Again, in Tamihana’s words. When he got back to Kapiti [from his last raid on the South Island] he told his people that they should go to Otakou and Rakiura to kill the men of Te Waipounamu. The idea that he should kill the men of that island lingered in Te Rauparaha’s mind for some time but it was not to be, for a new regime was coming.

The mission of the two young men was successful. The Ngai Tahu were prepared, despite their misgivings, to receive them, no doubt impressed by their reckless courage. Their assurance that Te Rauparaha would not return was accepted and, as Tamihana says, Ngai Tahu received the message of grace and forgiveness of God – ‘they believed in the word of the true God of Heaven’. There was to be no more war. There can be little doubt that if Te Rauparaha had had his way and attacked the remaining Ngai Tahu pa in Otago and Southland the tribe, which at this time had also been decimated by European epidemic diseases, would not have survived.

That Ngai Tahu did survive in the northern part of the island and rehabilitated themselves was also due to the influence of the Christian gospel. The captives who remained in Kapiti were returned to Kaiapohia and to Horomaka (Banks Peninsular). Under urging from Octavius Hadfield and also, no doubt, Tamihana and Matene, Te Rauparaha agreed to let the captives return. Banks Peninsula had been almost depopulated of Maori by Te Rauparaha’s raids and his sack of Onawe. Most of the freed captives returned there, re-establishing Ngai Tahu’s presence. Kaiapoi, with the return of the captives and fugitives from surrounding areas, re-established itself as a leading Ngai Tahu marae. When Bishop Selwyn travelled south with Tamihana Te Rauparaha in January 1844 to visit the communities which Tamihana had earlier evangelised, he found many groups of Maori who had become Christians. Some could read and, to quote from Selwyn’s journal, ‘many were acquainted with the Lord’s prayer, the belief and portions of the catechism.

Octavius Hadfield

After a brief period at Paihia, in the Bay of Islands, he responded to a request to establish an Anglican Mission on the Kapiti Coast. Hadfield’s strong sense of social justice often made him bitterly unpopular with the colonial government. For example, during the Taranaki war, he supported the rights of his Te Ati Awa converts. Hadfield’s attitude was based on his conviction that ‘every act in New Zealand must be productive of good or evil to generations to come’.

Hadfield suffered from severe asthma all his life, which often left him incapacitated and bedridden for months at a time. Despite his illness, he became Bishop of Wellington in 1870 and Primate of New Zealand in 1899.

Octavius Hadfield lived on the Marae, learned Maori and learned and embraced the cultural aspects of tribal living.Octavius Hadfield and Matene Te Whiwhi travelled in teams to the North and to Nelson & Blenheim areas to share Jesus. Octavius Hadfield helped protect Maori rights throughout the lower North Island and encouraged chiefs to sign the Treaty of Waitangi. He also was involved in justice issues wherever he saw Maori people being disenfranchised, making him, at times, unpopular with the government.He met the needs of the community by teaching reading and writing English and translating the Bible (with Rev Maunsell) into Maori. Hadfield nearly died on several occasions during river crossings, nearly capsized when crossing Cook Strait in a small boat. and through various illnesses. His Christianity was centred on being faithful to the call of God to preach the Word. He was a risk taker and did not fear death.It was a work birthed in prayer.

“My only trial at present is a want of time for reading and prayer, without which the soul cannot flourish. Now that I can speak the language my soul is indeed delighted with my work. The natives all along the coast call me their father. Yes, there is a kind of pleasure which is unutterable in the work. For instance yesterday in this place (Waikanae) to see about 500 persons who were but a short time ago buried in darkness and in sin, listening with the greatest possible attention while I was preaching from Romans 4:6-7 and in the evening on ‘I am the Good Shepherd’. Yes, on such occasions the Spirit sheds a fragrance on the soul, which leads one to forget one’s Fatherland and all the troubles of this life. However I feel deeply convinced of the necessity of setting apart much time for prayer in as much as ‘every man’s work will be tried with fire of what sort it is’.

Barbara MacMorran’s biography of Octavius Hadfield, (David Jones, 1969)

This is the only surviving remnant of Octavius Hadfield’s diary. It begins on 30 September 1839, at Paihia, and tells of the decision to send him to Kapiti, and his preparations for that journey. Suffering from poor health, he writes: ‘I may as well die at Kapiti as here.’ Hadfield’s diary describes in detail his overland walk from Wellington to Kapiti, including his first meeting with Te Rangihaeata, on Mana Island. He eventually arrived at Waikanae on 18 November 1839. The diary recounts his first encounter with Te Rauparaha, at Tahoramaurea, an off-shore island of Kapiti, and his meeting with the Ngati Raukawa, with whom he was to build the magnificent Rangiatea.